MEDIEVAL MUSIC AGAINST MODERN SOCIETY – Tote Bag

100% organic cotton, high quality print.

Frame design: 9th century, Milan (ms. BSB Clm 343, folio 17v)

Stop using plastic bags!

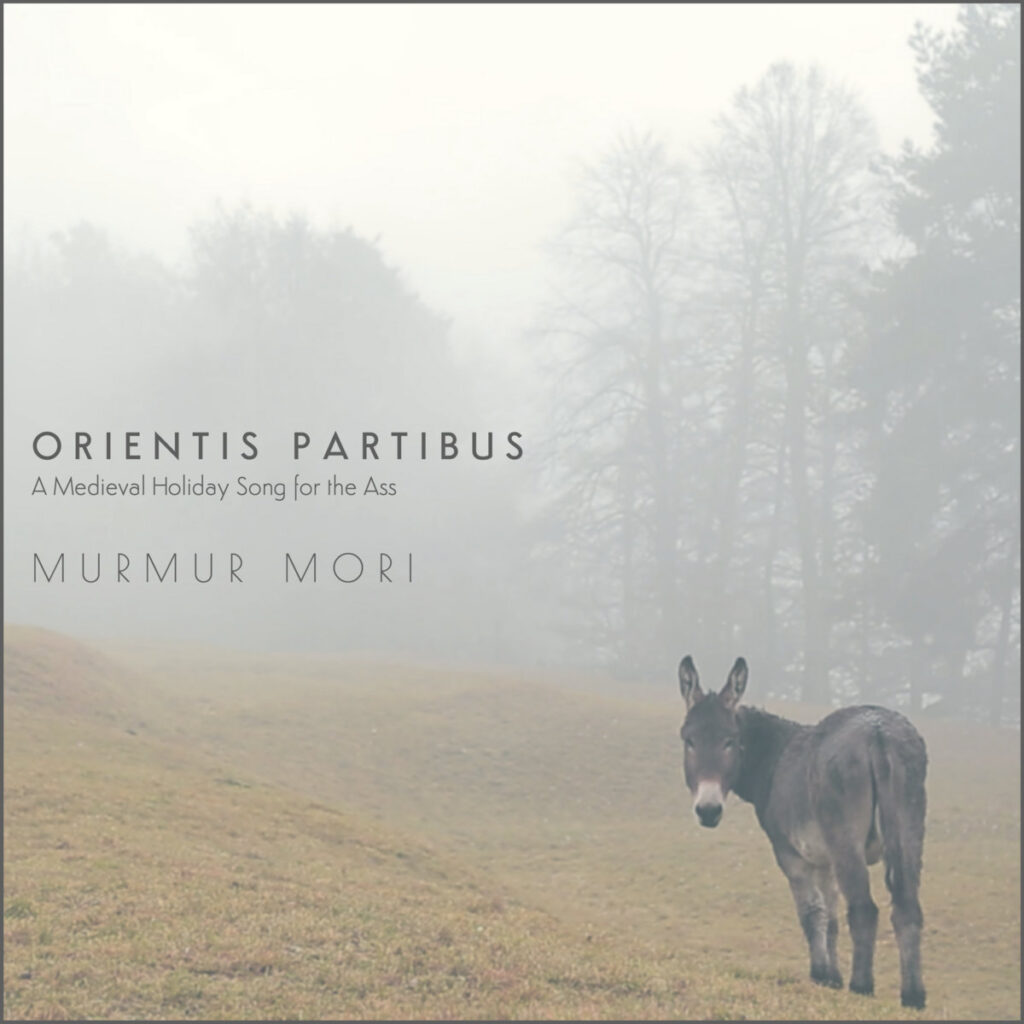

ORIENTIS PARTIBUS: A Medieval Holiday Song For The Ass

Songs for the holiday season? Here is Orientis Partibus, the ass song!

Which period, if not the Middle Ages, could have generated such an ironic and original song? Behind this composition, which dates back to the 13th century and is preserved within the manuscript "Officium stultorum ad usum Metropoleos ac primatialis Ecclesiae Sennonensis", preserved at the Municipal Library of Sens, lies one of the most incredible feasts of the medieval centuries: the "Feast of the Ass" strictly connected to the "Feast of Fools", probably a Christian adaption of the pagan Roman feast named "Cervulus". In the Middle Age there was a conception of the sacred and the profane very different from ours, and this feast, which goes so far as to dramatise the religious service itself including the participation of donkeys to the mass, makes an excellent example. It has to be noted that during the medieval centuries churches were multipurpose places in which, other than the celebration of the Holy Mass, gatherings and pacification of disputes took place; in times of need they also became hospitals for pilgrims and the sick, as well as shelters for the persecuted. It often happened that animals found their way inside, so it should not be surprising that, during particular feasts, clergymen danced near the tabernacle, while donkeys were led among the aisles and were adorned in sumptuous caparison.

Why all this happened?

In ancient times animals held great importance, and the donkey, being very much present in people's daily lives, was given many symbolic meanings. The donkey came to be identified as a symbol of "Goodness", being it as wise as Balaam's jennet and a patient mount not only for humble people, but also for prophets and Jesus himself; but the donkey is also a symbol of "Evil" since the times of ancient Egypt, being connected to Seth; Christians contrasted it with the ox, the symbol of Christianity, in Jesus' nativity hut. Because of his enormous phallus, he is also deemed to be pagan and desirous of the carnal pleasures of life, like Apuleius's Golden ass or Dionysus's. Jesus' triumphal entry in Jerusalem by donkey back represents the victory of Christianity over the ancient gods, and the cross the donkey carries on its back hints at the one carried by Jesus to Mount Calvary.

The ass was therefore celebrated during the winter holidays, and in an age of such wealth in art and music, songs were written for the donkey to accompany these processions in his honour. Orientis Partibus is one of them; it is attributed to the French the Archbishop of Sens Pierre de Corbeil, who lived between the 12th and 13th centuries. This is our ass shaking version: enjoy the listen, have a good winter!

Murmur Mori © 2024 – Edizioni Stramonium

Make love, not crusades: le canzoni di crociata degli amanti in partenza per la Terra Santa

Crusade songs for lovers departing to the Holy Land

"Amas e chantas soven", love and sing often, this is the advice given by Love to Peirol in the tenso he wrote and in which Love tries to convince him not to go on crusade; adding that “many lovers will depart, weeping, from their ladies”. What did people think of the Crusades? the popes proclaimed them, the monks preached them, knights departed and there were also women who participated, like the patroness of the troubadours Eleanor of Aquitaine. Then there were the merchants, who took advantage of the situation to establish themselves in the markets of the East and increase their profits. But who remained on the other side when someone sailed away? There are songs written to encourage people to travel, but there are also songs recounting us a very different point of view. The Italian Maritime republics played a large role in the Crusades, and a manuscript contains a woman's lament in early Venetian language which is heartbreaking in telling how she sees her house empty after the departure of her husband. Marcabru, in a poem that recalls both the "chanson de toile" and the “pastorela”, rhymes of when he met a woman crying near a fountain, she was cursing King Louis VII of France, promoter of the second crusade, that took her lover away. And even for men farewell was difficult enough to let them wish to stay, such as Chardon de Croisilles sang:"I am constrained to leave the one I have loved the most in order to serve the Lord God my creator, and yet I belong completely to Love". "Make love, not crusades" by Murmur Mori ensemble avoids giving entirely voice to those who promoted crusades, in order to shed a light on the sources and songs, including some early Italian vernacular lyrics, of those who suffered and waited for Love to return.

Murmur Mori © 2024 – Edizioni Stramonium

CRUS OCELLE MEUM VELLE: una canzone d’amore del Nord Italia dal secolo XI

11th century love song from Northern Italy

A melody and profane lyrics from 1000 years ago, contained in a single manuscript from Northern Italy composed between Lodi and Novara. The musical notation above the Middle Latin text of manuscript Vat.Lat.3251 is semidiastematic and the pitch of the note F is indicated.

This is the first complete recording of this song.

Under green foliage filtering the light of the morning sun, or perhaps within the walls of a cold and calm 11th century scriptorium, an anonymous hand wrote the carmen amatorium “Crus ocelle meum velle”, a love lyric that is almost hermetic in its language rich in allusions and esotericism: a sweet succession of melancholic and marvelous images blooming heavily in their innocent desperation, those who listen to the verses are invited to love before losing youth's bloom and rotting, and the betrayed faith is compared to a brutally cut oak which, even if replanted, is no longer going to generate new leaves.

Murmur Mori © 2024 – Edizioni Stramonium

O ADMIRABILE VENERIS IDOLUM: una carmina italiana del secolo XI

A 11th century carmina from Northern Italy carmina dell’XI secolo proveniente dal Nord Italia.

The lyrics of this latin love song, probably of Veronese origin, is addressed to a young man who is about to embark on a journey and will cross the Adige river. The poet addresses words of love to him, is saddened by his distance and invokes pagan deities such as Neptune, Thetis, Clotho and Lachesis so that they can protect him on the way. The melody comes from the cod. 318 of the Abbey of Montecassino, and the metre of the lyrics was based on the Christian pilgrims' chant "O Roma nobilis", with which the composition appears related in the manuscript sources that have come down to us.

Murmur Mori © 2024 – Edizioni Stramonium

Canzoneta, va!: poesia e musica tra Francia ed Italia nei secoli XII e XIII

"Canzoneta, va!" poetry and music between France and Italy in the 12th and 13th centuries.

Courtly love and chivalry in the lyrics of the ancient troubadours. The Provençals Raimbaut De Vaquerais, Aimeric de Peguilhan, Guillelma de Rosers, Giraut de Borneill are some of the many who introduced courtly poetry in Provençal language to the Italian courts, influencing Italian troubadours, jongleurs and poets such as Sordel, Lanfranc Cigala, Gherardo Patecchio and other authors, even anonymous who started to use their own italian vernaculars inspired not only by the provençal but by the chanson de geste of northern France. Their works finally resonate thanks to the research and performance of the Italian ensemble MURMUR MORI.

Murmur Mori © 2023 – NovAntiqua

Dançando la fressca Rosa: ballate e poesia giullaresca

The libri memorialium from the Bologna State Archives were written by notaries and they contain ballate and rhymes which are among the earliest poetry in the vernacular from Italy such as the ones contained in the manuscript Vaticano Latino 3793. Most of these poems were intended to be sung and played and in fact, even if are handed down to us in manuscripts without musical notation, they still have textual indications about their musical forms. Murmur Mori set these fundamental early Italian lyrics to music using medieval instruments, merging the Italian folk music heritage together with the medieval manuscript sources of secular music, to rediscover their sound and avoid them to be merely confined in literary studies. The music here presented focuses on jongleur poetry of the 13th and 14th centuries and on the musical form of the ballata. Chants of love, satire and to dance to. The 16 pages booklet have an introduction by prof. Tito Saffioti.

Murmur Mori © 2022 – Edizioni Stramonium

Concerto a Montorfano

L’alba del volgare Italiano

13th century poems and lyrics from jesters set to music, songs inspired by Nature and poems from the Codex Buranus. A live album recorded inside the medieval church of San Giovanni in Montorfano, in the Italian Alps. The entire video is viewable on our YouTube channel. Download includes a 12 pages English/Italian booklet with photos and detailed informations about the songs and the lyrics.

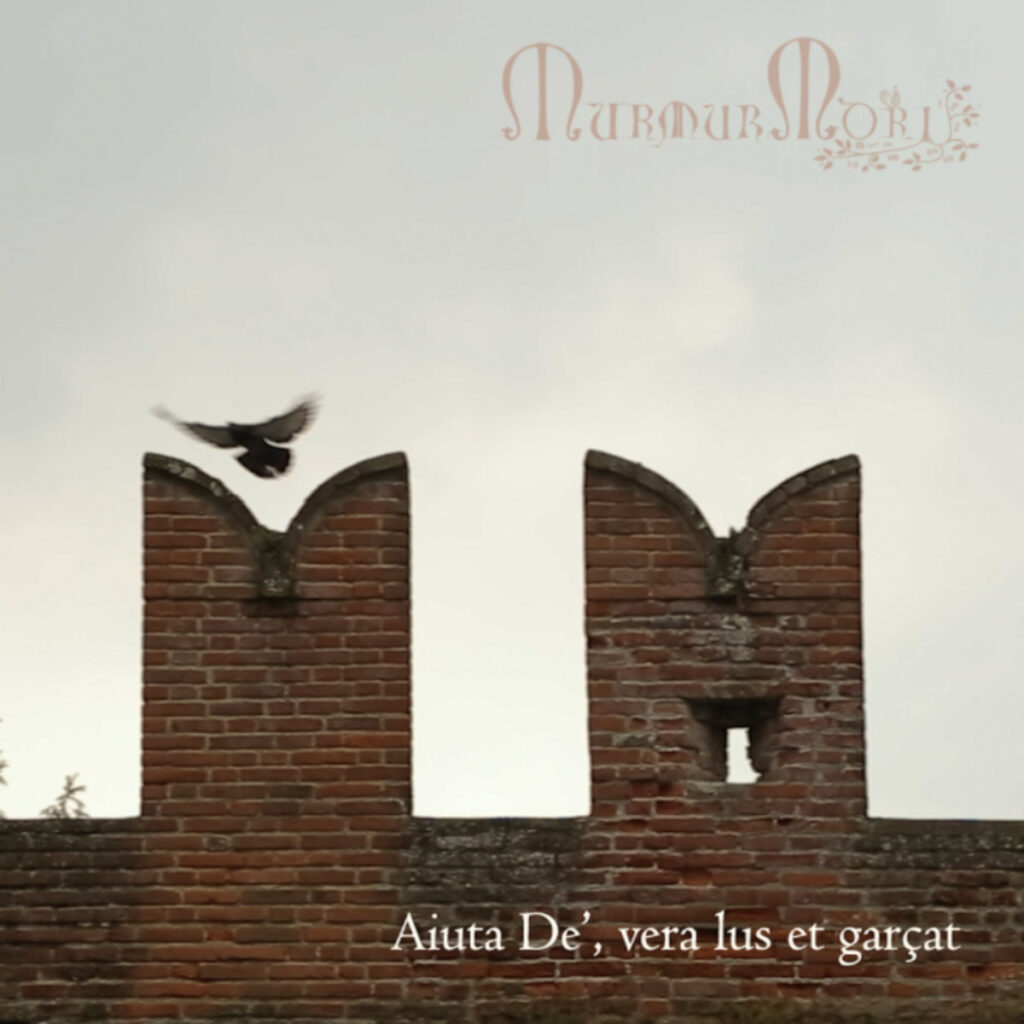

Aiuta De’, vera lus et Garçat – Rex Glorioso

The Alba (sunrise) was a very popular poetic genre in the 12th and 13th centuries, in which two lovers, after a night of love, are in torment for the arrival of dawn, the daylight is the moment in which they must separate rapidly if they do not want to be discovered by the “Gilos”, her husband. It has to be remembered that in the past marriages did not take place for love and, according to the laws of Courtly Love, it was accepted for a woman to have only one lover, chosen for true and sincere love, in addition to her husband. Often in these compositions the verses were sung by a fourth figure, called "sentry". It could be a male or a female and had the task of watching over the two lovers and waking them up quickly in case of problems or at sunrise if they weren't awake. The most famous alba that has come complete with music is that of Giraut de Borneill, a troubadour born in Aquitaine, called by his contemporaries "master of the troubadours". The geographical borders in the 12th and 13th centuries were very different from today and from Provence this successful musical and poetic motif also reached northern Italy. “Aiuta De'” is the translation of Giraut's Occitan composition “Rei glorios” into a Piedmontese vernacular, written in the thirteenth century, before 1240, and preserved in the manuscript E 15 sup. of the Ambrosiana Library in Milan. Dating from around 1240, this document is a proof of the fact that this piece was well known in northern Italy. Murmur Mori's version combines the Italian text with the music of the one wrote by Giraut de Borneill contained in the ms. Français 22543 of the National Library of France. Unfortunately, in the Italian text the last verse is illegible, the ensemble wanted to fill this gap with the singing of a morning bird.